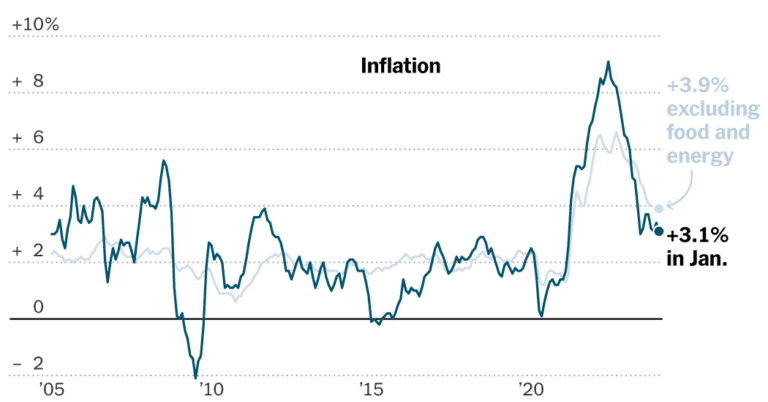

Inflation eased less than expected in January and showed worrying staying power after stripping out volatile food and fuel costs – a reminder that controlling price rises remains a difficult process.

The overall Consumer Price Index rose 3.1 percent from a year earlier, which was down from 3.4 percent in December, but more than the 2.9 percent economists had forecast. This is down from the last peak of 9.1 percent in the summer of 2022.

But after stripping out food and fuel, which bounce in prices month-on-month, “core” prices were almost flat on a year-on-year basis, up 3.9 percent from last year. The measure climbed the most on a monthly basis in eight months.

Federal Reserve officials welcomed a recent decline in inflation and will likely take the new report as confirmation that they should remain cautious. Policymakers have been careful to avoid declaring victory over inflation, insisting they need more evidence that inflation is coming down sustainably.

Investors sharply reduced the odds of an imminent rate cut after the data, betting that the Fed would not cut rates at their next meeting in March and sharply retreating the odds that it would even do so at their next meeting in May. — a sign they believe the new inflation data will keep officials cautious.

Fed policymakers have raised interest rates to around 5.3%, from near zero in early 2022, in an effort to dampen consumer and business demand and force companies to stop raising rates so quickly. Because inflation has fallen significantly in recent months, they have halted their interest rate hikes and are considering when and how much to cut borrowing costs.

But they want to avoid cutting interest rates before inflation is completely gone, because they worry that doing so could allow rapid price increases to become a more permanent feature of the US economy.

“They are right to be patient because this is the number that is going to call into question whether there really is much of a slowdown for inflation,” said Omair Sharif, founder of Inflation Insights. “That’s certainly a scary number.”

Slower inflation in recent months has also been a welcome development for President Biden. Rising living costs have eaten into household budgets, weighing on voter confidence even as the labor market is strong and wages are rising rapidly. As price increases have begun to ease, people are starting to report a sunnier economic outlook.

The question for both management and the Fed is whether the easing of inflation over the past six months can last — and the new inflation report may keep officials cautious.

“Does it send us a real message that we are, in fact, on a path — a sustainable path — of 2 percent inflation?” Jerome H. Powell, chairman of the Fed, said during his January 31 press conference. “That’s the question.”

The Fed targets inflation of 2% on average using a separate but related measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditure index. The January reading of this gauge is scheduled for release on February 29.

Inflation is coming down for a variety of reasons, but a big driver of the recent improvement has been the healing of global supply chains. Commodity prices began to rise in 2021 as shipping and factory disruptions linked to the pandemic left semiconductors, cars and furniture in short supply.

These problems have slowly cleared up, and commodity prices have recently eased — and, for some products, fallen. Used car prices fell sharply in January, for example.

More recently, price increases for basic services have also begun to moderate. Economists are now watching closely what happens to one in particular: housing. Rent increases have started to slow in the official inflation data, but many analysts expected that trend to deepen as cheaper new leases slowly feed into the official data.

But on this point, January’s report offered reasons for caution. A measure of how much it would cost to rent a home that someone owns – called landlord equivalent rent – collected on a monthly basis.

The acceleration “seems at odds with other surveys of rental data that we track,” said Blerina Uruci, chief U.S. economist at T. Rowe Price.

Still, the data means the Fed should remain cautious — and that officials are unlikely to cut rates until May or June.

“They really need to make sure that inflationary pressures don’t pick up again before they can cut rates,” Ms Urucci said.